When it comes to important topics, food is an absolute necessity. We literally cannot live without it. For those of us fortunate to be alive today, it’s also overwhelmingly easy to forget its importance. Never in human history have we had such a wide variety of cuisines to choose between, so many places to buy it from or number of ways to prepare it. But that luxury of choice can breed negligence, especially when it comes to knowing where our food comes from and the impact it has before it arrives on our plates.

I recently watched the activist documentary Cowspiracy and was shocked by the claims that agricultural emissions were the number one cause of climate change. The take home message was that changing your diet will have a a bigger impact on the planet than cutting out all of your fossil fuel use.

It is a powerful message and indeed was partially responsible for my transition to a primarily vegetarian diet. But as a journalist I rarely take things at face value and keeping in mind this was a documentary with a specific agenda I felt obliged to investigate further.

Cowspiracy’s first claim is that “animal agriculture is responsible for 18% of greenhouse gas emissions, more than the combined exhaust from all transportation”. In other words, all cars, planes and trucks on the planet emit less greenhouse gas than the animals we raise for food.

The source for this statistic comes from an influential study conducted in 2006 by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). It’s a reputable source and is backed up by figures from the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) and the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency).

In fact since 2006 that figure has increased (when combined with forestry and land use) to 24%, as shown in the chart below.

Source: IPCC (2014); EXIT based on global emissions from 2010. Details about the sources included in these estimates can be found in the Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

What Cowspiracy overlooks is that although animal agriculture does contribute almost a quarter of global emissions, the areas of industry, electricity and transportation still emit a far more weighty 60% of greenhouse gasses. So while animal agriculture should be a concern, it is definitely not the only concern.

The documentary’s far more explosive claim is that “livestock and their byproducts account for at least 32,000 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) per year, or 51% of all worldwide greenhouse gas emissions“.

This statistic is directly at odds with the figures above, so where does it come from?

The source is a scientific paper which argues that the methods used by the FAO do not take into account the full range of emissions caused by animal agriculture. To summarise the main points, the FAO did not account for:

- emissions from livestock respiration (eg. CO2 exhaled) = 13.7%

- the potential use of land cleared for agriculture to offset emissions = 4.2%

- methane emissions using a 20-year instead of 100-year timeframe = 7.9%

- undercounted statistics and data = 18.7%

All of these areas certainly have some merit and are worth further investigation, but I would be inclined to use it as additional information rather than hard data. For comparison another study in 2012 included fertiliser manufacture and refrigeration emissions in its calculations to arrive at a global emissions figure of 33%.

To me it seems obvious that while the definition (and therefore statistics) of agricultural emissions may vary, the impact is certainly significant. But I would hesitate before making the claim that it’s over half the world’s total emissions.

Feeding the World

So having established that there is a problem, just how important is animal agriculture to the world?

Developed (or to be more specific OECD) countries consumed an average of 69.7kg of meat per person in 2017. Remember this statistic counts all of the non-meat eaters as well and combines countries like the U.S. (98.6kg) with Japan (36.4kg), so the actual amount per omnivore is almost certainly higher.

Source: YouTube 2017 How to Butcher an Entire Pig: Every Cut of Pork Explained

As a visual representation OECD meat consumption is equivalent to one pig per person per year; about 1.34kg of meat per week or roughly 200g per day. That may not seem like much, but is still a third greater than government dietary guidelines recommend for a healthy lifestyle. Meanwhile in developing countries meat consumption is increasing by an average of 3% every year.

Disregarding the environmental impact of producing all this meat for the moment, there’s even more bad news for carnivores because compared to plant-based products, meat is an extremely inefficient use of calories.

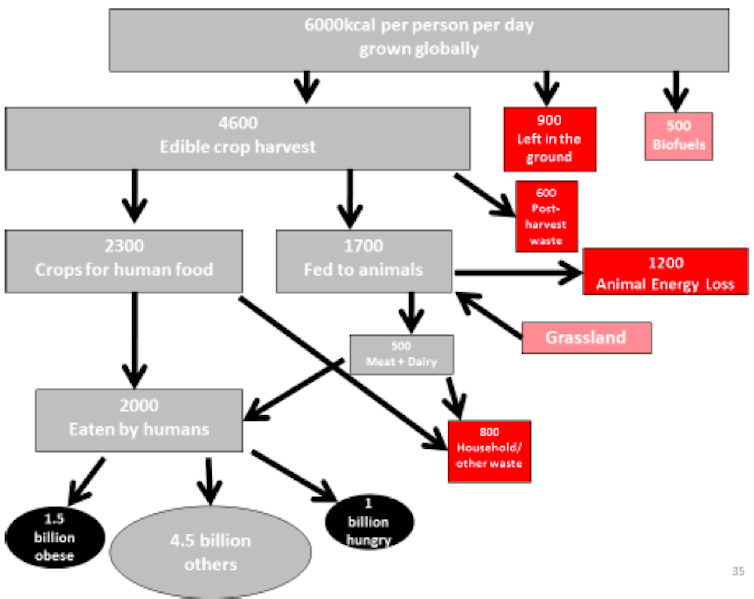

The average human needs around 2,500 calories per day to maintain a healthy weight. Currently the world produces 6,000 calories per human per day, which seems like more than enough. But a single calorie of meat requires almost 3 1/2 calories to produce. Coupled with agricultural and domestic food waste, an energy-to-protein requirement of anywhere up to 57:1 and suddenly just under a billion people are left hungry every day.

A paper published in Science last month shows that animal farming takes up 83% of the world’s agricultural land, yet provides just 18% of our calories. In short if the plant protein currently fed to animals was fed to humans instead, we’d have over a third more food to eliminate world hunger.

The logical next question is; do we need meat at all?

A large number of studies agree that vegetarian and lacto-vegetarian diets are linked with health benefits such as lower cholesterol and reduced risk of heart disease and cancer. But those diets can also be lacking in essential nutrients, with vegetables unable to provide several key nutrients like Vitamin B12 and creatine.

Supporters of omnivorous diets point out that meat combines complete proteins, amino acids and essential vitamins like B12 all in a neat and tidy package. Indeed this ease of nutrition is probably why humans became carnivores in the first place. A Nature study in 2016 found that eating meat saved our ancestors 13% more energy, meaning that our brains could develop faster and become larger.

However the study also admits that none of those reasons are relevant today in a world where we don’t have to prepare our own food, let alone catch it. With vitamin supplements available and most of the food processing taken out of the equation, it looks like meat’s main drawcard is that it allows for lazy shopping.

Which brings us to the main stumbling block in moving to a meat-free world; education.

Source: Youtube 2015, Meat Your Future

Raising the Steaks

Cutting meat out of your diet requires at least a fundamental knowledge of nutrition. Knowing what you need to eat in order to get sufficient protein, vitamins and nutrients takes some effort. For the 4 billion people connected to the internet, it’s not too much of a problem. But for the other half of the world it might be.

As this 2015 study shows, meat consumption in developing countries is linked to positive health effects. The same study also shows that in developed countries meat consumption has the opposite impact, due to higher consumption of fat, sugar, processed foods and less fibre.

This evidence seems to suggest that developing countries can benefit from meat until they reach a sustainable point, at which stage they should move toward a meat-free society.

So the onus is on us in the developed world to change our eating habits, because with meat consumption growing faster than the overall population it seems self evident that the Earth cannot continue to support a population of 7 billion people and the 70 billion animals we use for food.

The first step has to be education. Most people in developed societies grow up learning that a basic meal consists of meat and veg. The thought of replacing chicken with tofu; or mincemeat with kidney beans would never have crossed most kids’ minds growing up in such a household.

Source: FitFormula

A more sinister trend is the steady increase in ultra-processed foods such as ready meals, snacks and soft drinks. A staggering 50% of food bought by UK families falls under this category and has worrying health consequences. It’s clear food education needs to improve, but how?

Firstly school education programs play a critical role, but need to be supported by both the lunch canteen and family at home in order to have success. It’s not much use teaching children about nutrition and then selling junk food cheaper than healthier alternatives. Similarly studies show children who take home cooking materials and have actively engaged parents are the most likely to learn.

Secondly governments, supermarkets and food outlets must take greater responsibility in educating consumers about food nutrition. Compulsory, simple nutrition labels would increase public health and could also provide information about what nutrients are both present and missing from certain products. That way people switching to a vegetarian diet could see what they were lacking and compensate accordingly.

Finally we, the consumers, have a responsibility to increase awareness around the impact our diets. At home you can begin to introduce vegetarian options to the weekly meal plan; or ask your primary chef if they wouldn’t mind experimenting. When eating out you can discuss food sustainability with your friends and loved ones. If you learn something interesting you could share your thoughts online, in a blog (wink, wink) or on social media. Lastly, when filling up that shopping trolley you can take a moment to think before you buy.

We are what we eat…and also what we don’t.